‘Dear St. Eugene’: Residential Schools, Public Engagement and the Erasure of Trauma in (a Post-Truth and Reconciliation) Canada, is a project funded by the Public Humanities Hub Okanagan Impact Awards. The project examines the negative heritage site of the St. Eugene Catholic Mission residential school, located in the interior region of British Columbia. Negative heritage sites are places associated with conflict, trauma, or disaster for the individuals and communities who know them.

Team members, Lindsay Der (PI), Haley Seven Deers, Jordanna Marshall, Shanneen Chiu, Camille Morissette and Alicia Bondar, introduce the project below.

TRIGGER WARNING: This blog post contains information about the Residential School System that may be disturbing or triggering to survivors and/or their families.

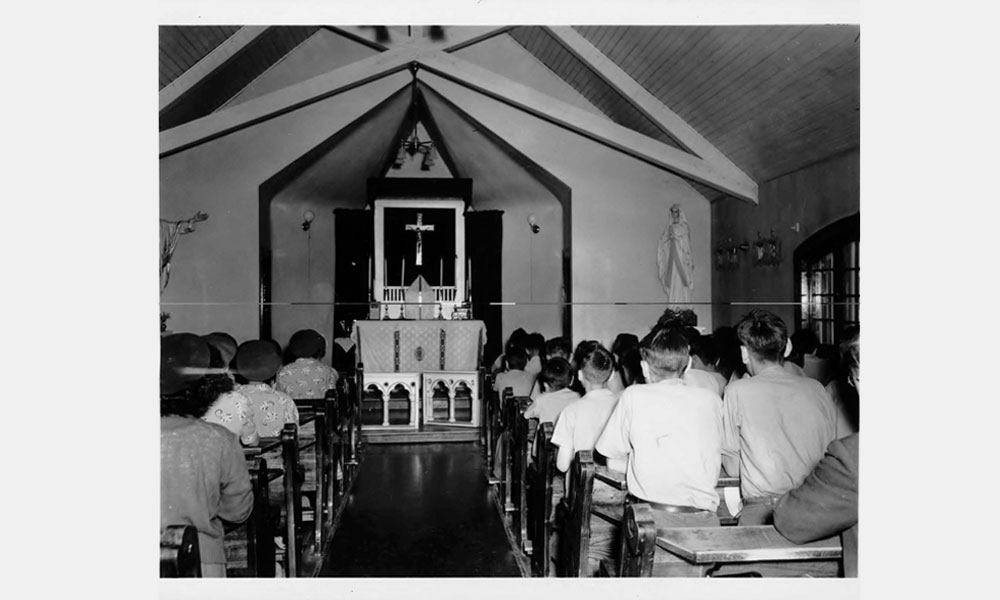

St. Eugene Church interior. Photo source: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

Places are rooted in history. But how do spaces transform in the collective consciousness as new meanings and associations are connected to them? More specifically, how are places of trauma remembered or forgotten over the passage of time? And what strategies do people choose to deal with such sites?

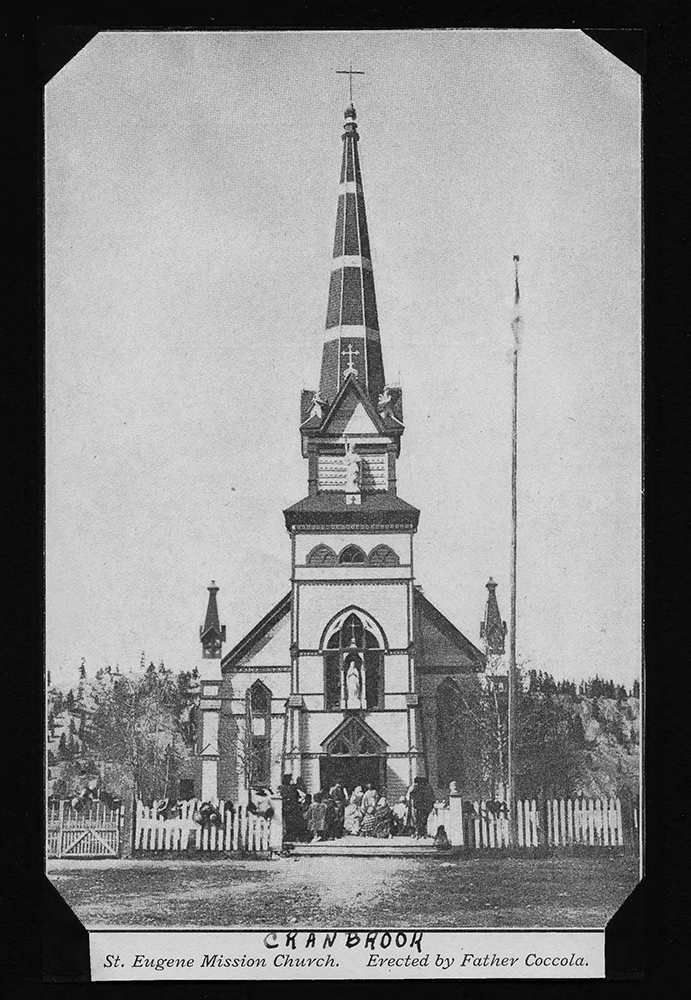

Established at the end of the 19th Century, residential schools were government-sponsored Christian schools designed to assimilate Indigenous children to the Euro-Canadian culture. Approximately 150,000 children, across 130 schools, were forced into these institutions. Emotional, sexual, and physical abuse took place at these schools and 6,000 children are estimated to have died during their “re-education”. The last Canadian residential school closed in 1996, however, the effects of the government’s oppression continue to persist today on an intergenerational scale. Although St. Eugene is one of the few residential schools still physically standing in Canada, in the years since its closure, it has been transformed and repurposed by the Ktunaxa Nation.

Through interviews with members of the Ktunaxa Nation and the Sylix Nation, whose children were sent to St. Eugene, this project asks why groups choose particular heritage management strategies and how theses strategies may or may not contribute to the healing of trauma. It will also shed light on how power dynamics affect the ability of Indigenous communities to manage, conserve, and/or control their own negative heritage. As well, members of the public, including residents directly connected to the site and legacy of residential schools, will be invited to interact with a digital story map online, to learn about the site and to write postcards to St. Eugene, expressing their views and thoughts. In this way, the project aims to measure and raise awareness of and facilitate discussion on Canada’s colonial history so that such atrocities will not be repeated in the future.

Due to COVID-19, the team has been busy spending the last few months prepping to move the project online and to gather data remotely. In the coming months, they will be working to establish relationships with members of the Ktunaxa Nation and Sylix Nation. They are currently in the process of building a website to host the postcards to St. Eugene – please keep an eye on this space, as well as @negativeheritageproject, negativeheritageproject.org and @amplab_ubco for updates.

St. Eugene Mission Church. Photo source: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

A Residential School Survivor Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former Residential School students. Emotional and crisis referral services can be accessed at 1-866-925-4419.