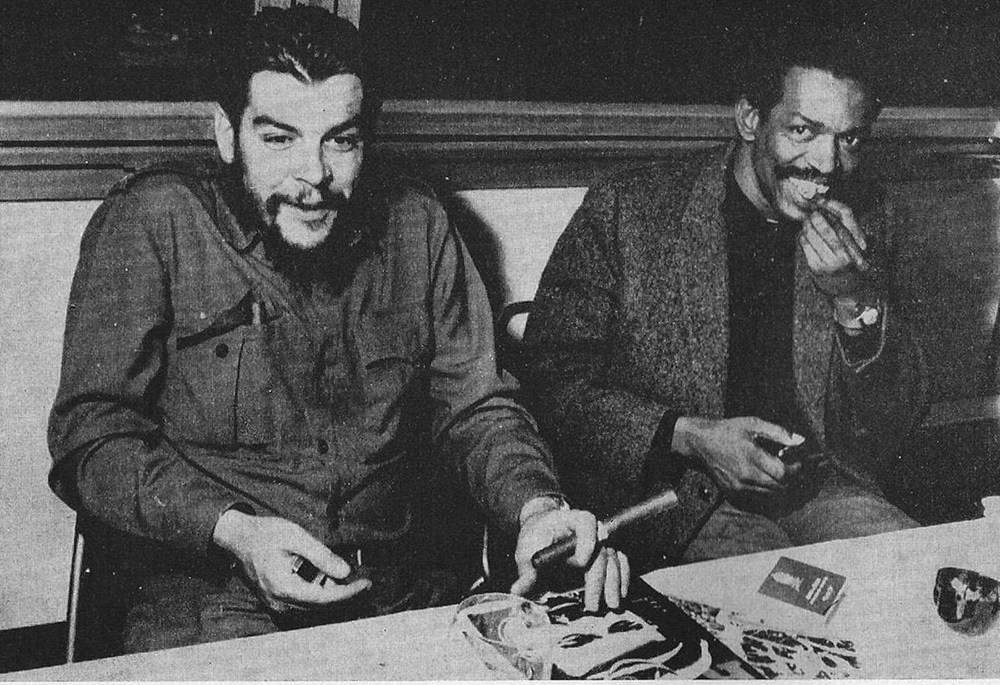

Che Guevara and Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu during a political meeting in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania). Source: OSPAAAL historical archive (La Havana, Cuba).

UBC professor Jessica Stites Mor is collaborating with Fernando Camacho Padilla, a professor from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid through the Public Humanities Hub Joint Fellowship Program (PHJF), on a project titled, Visualizing Solidarity.

With this project, they will work to provide an entry point for those that are interested in the history of the Cold War to learn how photographs were used to produce tangible connections of solidarity.

They have provided the following update on the progress of their project.

Much has been written about the graphic production of OSPAAAL, especially with respect to poster art (See article). The influences of OSPAAAL’s work, beyond transmitting solidarity, can also be seen in the artistic production of different revolutionary organizations around the world during the Cold War. Conducting our research as a part of the Public Humanities Hub Joint Fellowship, we were able to access OSPAAAL printed material, posters, issues of the Tricontinental magazine and bulletin, and related material. In addition, we found a wide range of scholarship on the subject, most prominently in Spanish, English, French and Arabic language scholarship. However, the influence of these materials was also documented by scholars working and writing on revolution and decolonization in Italian, German, Vietnamese, and Portuguese.

Leftist activists all the way from Scandinavia to Argentina, including countries such as Iran, Lebanon, and Egypt, seem to have been interested in reading the different contributions of the publications and in decorating the walls of their apartments or offices with posters. Perhaps as a consequence of the popularity of these materials, the governments and dictatorships that were targeted by critiques of OSPAAAL, including United States, France, Great Britain, Portugal, Israel, South Africa, Rhodesia, Morocco, China, and El Salvador, among many others, were also interested in the publications. So, we began to investigate how these governments responded. We were curious to know the extent to which each were concerned about the work OSPAAAL was doing in extending solidarity narratives across so many borders.

After visiting the diplomatic archives of some of these countries, we can conclude that the circulation of OSPAAAL printed material also reached and was carefully studied by Castro’s international enemies. Intelligence services collected each poster and each number of the Tricontinental magazine and bulletin, sometimes directly from their embassies in La Havana. They read them with interest and transmitted reports on the information they contained to state departments and other interested parties, particularly when OSPAAAL’s publications related directly to their own national interests. Many governments spent time analyzing and commenting on the contents of the publications. Portuguese agents, for example, followed all the publications in relation to Cuba’s support to the different National Liberation Movements which were active in Portugal’s colonies in Africa. Likewise, Israel did the same in relation to Palestine, South Africa with respect to reporting on apartheid, Morocco about West Sahara, and El Salvador about the civil war and support to the different left organizations. The Tricontinental magazine was also eventually forbidden in France.

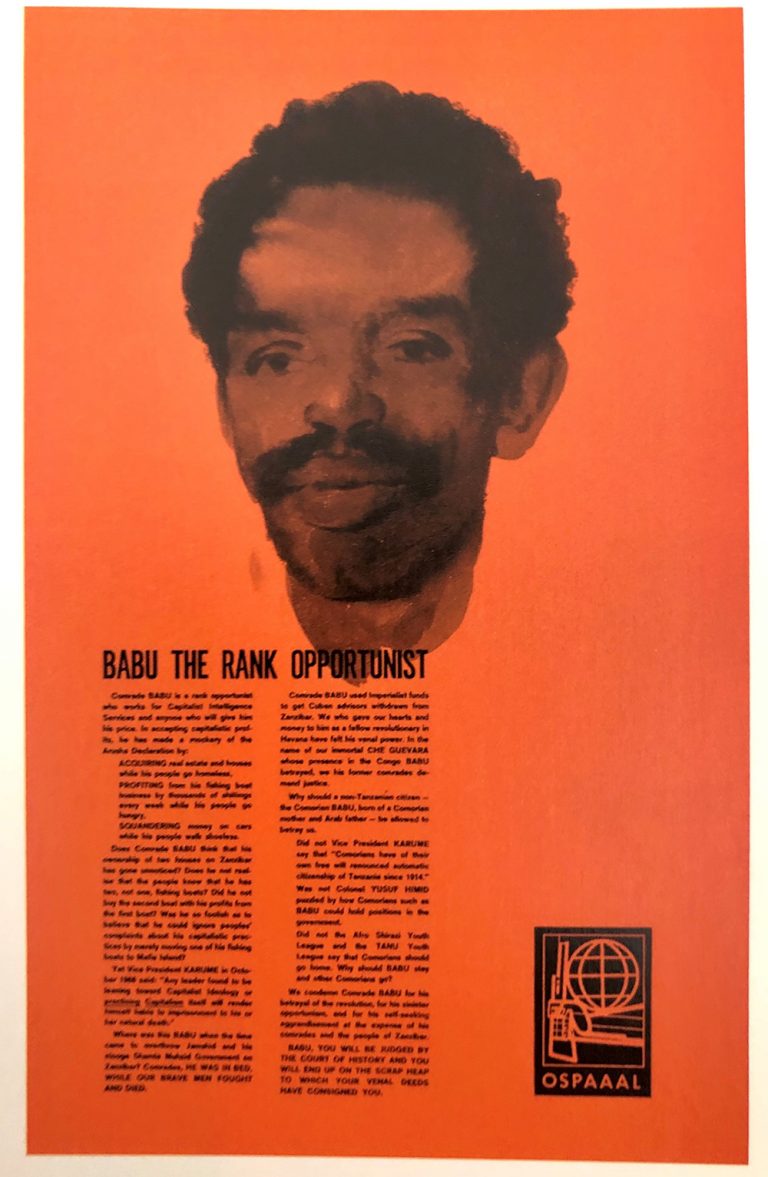

The artwork produced as part of Cuba’s international solidarity also worried key figures within these intelligence and diplomatic services. They noticed and commented on the power of the graphic art, specially the OSPAAAL posters, and frequently tried to censor them. However, other strategies were implemented as well. For example, several enemies of the Cuban revolution printed imitation OSPAAAL posters in order to cause confusion and discredit Cuba’s solidarity actions. For example, in Babu the rank opportunist, a fake OSPAAAL poster was printed to attack and humiliate Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu. Babu had assisted Che Guevara in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) during his African tour, and also visited Cuba in 1964. Printing counterfeit posters, they imitated the style of the OSPAAAL’s artists and used the organization’s logo. Such attempts were aimed at misleading audiences about Cuba’s political position and provide evidence that Cuba’s solidarity work was considered significant in shaping revolutionary consciousness.

Fake OSPAAAL poster about Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu. Image Source