Fernando Camacho Padilla and Jessica Stites Mor

Visualizing Solidarity: Cuba’s Commitment to the Global South in Photographs

UBC professor Jessica Stites Mor is collaborating with Fernando Camacho Padilla, a professor from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid through the Public Humanities Hub Joint Fellowship Program (PHJF). The PHJF supports researchers in realizing a short-term research and/or creation project, with a deliverable to be presented at the UBC Okanagan Public Humanities Conference this July.

With this project, they will work to provide an entry point for those that are interested in the history of the Cold War to learn how photographs were used to produce tangible connections of solidarity. They also anticipate that the project will bring to light stories that have otherwise been forgotten. These stories of encounter and exchange between participants in solidarity actions provide us with more knowledge about the means by which people within the Global South worked together to oppose powerful common enemies.

About the project

From 1961 through the early 1990s, Cuba’s revolutionary government committed itself to national liberation causes in Africa, Asia, and Middle East. By 1976, over 30,000 Cubans were actively involved in military, educational, and medical missions as part of Cuba’s internationalist solidarity mission. Cuba’s direct intervention in places like Angola, Syria, and Algeria was praised by some leaders, such as Nelson Mandela. However, it was considered threatening to some within the Non-Aligned Movement and the United Nations, where Cuba’s interests and connections with the Soviet Union were the object of some suspicion.

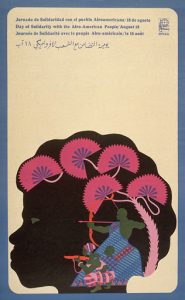

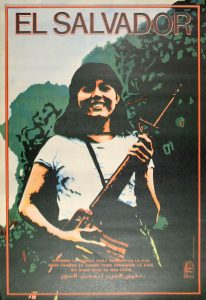

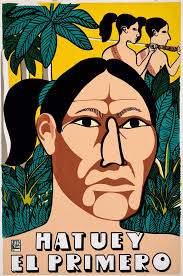

Sending direct military and humanitarian assistance were not the only means by which Cuba signaled its willingness to advance internationalist revolutionary objectives. Cuba also founded the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (OSPAAAL), which quickly became a conduit of revolutionary ideas. It circulated updates on national liberation struggles and calls to action for solidarity, through a monthly newsletter, the Tricontinental Bulletin, and a bi-monthly magazine, the Tricontinental. These publications included interviews, news reporting and analysis, speeches and essays, alongside colorful posters, and photojournalism. They communicated visual evidence of Cuba’s involvement in distant struggles for liberation.

With this project, we hope to explore the role of visual communication and photojournalism in the printed work of the OSPAAAL. We are curious to find out how Cuba’s campaigns to promote a particular interpretation of the Cold War were coded into photographs and visual aspects of journalism. And we are also interested in seeing how depictions of solidarity activities were used to build confidence in Cuba’s position in international conflict.

While it is clear that Cuba was also using these means to garner support for the revolution, we are interested in how the spirit of Cuba’s interpretation of anti-colonialism, anti-racism, and liberation were captured in images that communicated specific moments in time. In particular, we have been looking at images of participants and combatants, captured in rare moments of exchange with Cubans that travelled to offer assistance in local struggles.

We are also curious to see how women and children are presented within images meant to communicate revolutionary aims. We will analyze photos that depict Dhofari soldiers trained in South Yemen, photos of patients that attended at a Cuban sponsored hospital in Western Sahara, Angolan educators upon receiving equipment from their Cuban counterparts, and think about how these images depict the relationships between instruments of revolution and each other.

Posters art of the Organization for Solidarity with African, Asian and Latin American Peoples, printed in Havana, Cuba, and circulated via the Tricontintnental Magazine